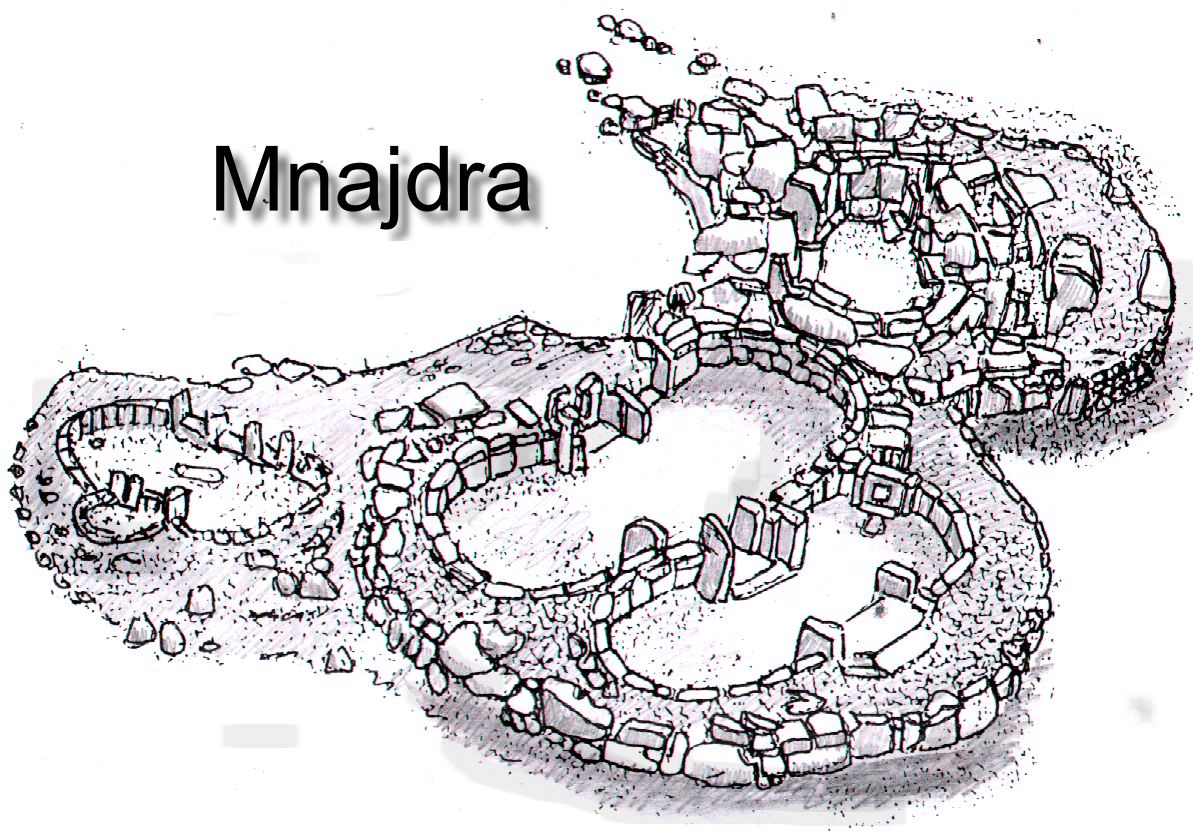

About half a mile to the west of ‘Hagar Qim” on a small terrace overlooking the cliffs and the sea, stands another group of megalithic ruins, first excavated in 1840, described in detail by Mayr in 1898, and carefully re-examined in 1908. These consist of three groups of buildings independent of each other, with separate boundary walls, and on different levels.

The entrance to the higher or northern building faces southeast and is place at right angles to the main wall. The first space is an elliptical area, fifty-four feet in length, with well-finished walls made of a course of slabs placed on end and surmounted by two courses of blocks. There are no niches in this room, but two recesses, formed by uprights in front of the entrance may have contained pillars or statuettes.

The walls of the next elliptical area are similar to those of the first one. A deep recess, enclosed by six slabs placed on end, faces the entrance. Two vertical stones at the sides support a large slab about ten feet by four. At the southern end of this area a highly finished window-like entrance leads to a niche constructed at a lower level, filled by an altar-table consisting of a slab of stone supported in the middle by a cylindrical pedestal.

Leaving this building, one walks down to the lower one, adjoining the first building at its southwest corner. This second building has a paved forecourt and a series of rectangular blocks placed along the façade apparently intended to afford sitting accommodation for worshippers. The walls are made of unhewn blocks of coralline limestone, a hard stone found in the neighbourhood; at Hagar Qim, a softer and lighter limestone was used.

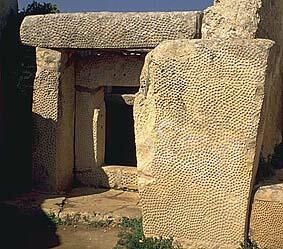

The entrance, carefully constructed of large slabs, is covered by a lintel nearly ten feet long by four feet broad, and is paved with flagstones. The lintels have numerous holes for wooden bars or ropes. The large area, reached through this passage, is over forty-five feet long and twenty-three feet wide. A stone slab, six and a half feet long, is fixed at the southern end of the apse and a recess in the left wall contains a trillithon, or table-like construction, five feet two inches high, with a lintel nine feet nine inches long.

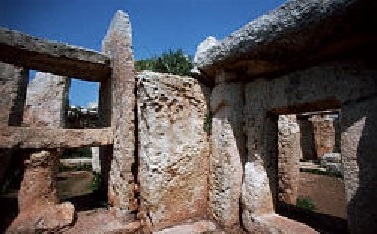

To the right of the northern apse, a window-like opening leads to a triangular room at a higher level. At the southern end of this room a graceful niche with a window-like opening, contains a shrine made of well finished slabs of stone resting on a slightly bulging pedestal very carefully worked.

In the lower area to the southwest, a very elaborate doorway leads to a room, which appears to have been peculiarly sacred. The pillars, lintel, and slabs forming the doorway are highly finished and elaborately pit marked. The room is rectangular, with niches to the north, south and west. Each niche is formed of a pair of uprights with a block laid across their tops, while a table in the western niche is further propped by a central pillar.

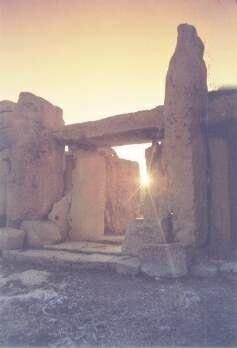

Facing the main entrance of the temple, in the main area, is a well-built and well-paved passage, leading to a small rectangular room. This passage was once covered with long slabs, on of which, pierced in the center by a round hole, now lies on the floor of the large area. In the middle of the passage is a similar hole, which would correspond to the hole in the lintel if the latter were in place. The two holes received probably the pivots of swinging door.

The room at the end of the passage contains a rectangular niche with a fine trillithon, of which the horizontal slab is nearly ten feet long. The adjoining room to the north, at a slightly higher level, is not so well finished as the others. In this room several clay figures representing diseased parts for the human body were found, under the floor of beaten earth, suggesting that the place was sacred to a healing deity.

A splendid collection of objects obtained from these ruins in 1908, and now preserved in the Valletta Mus eum, shows that Mnajdra belongs to the same stage of civilization as the Hagar Qim and Gozo sanctuaries.

An edging within the central temple shows what is believed to be roofed temple.

Could these temples have been roofed at some time? If so, what has happened to the top two tiers of the temple’s structure?

Were these tiers made from a flimsy material covered in soil that may have perished over the years? Questions that may remain unanswered for the time being.

Mnajdra Temples date back to the Ggantija phase (Circa 3600-3100 B.C.)