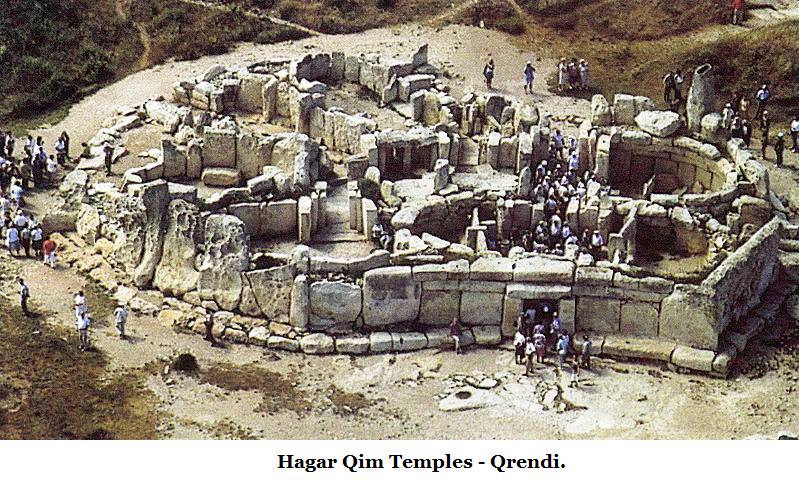

The name Hagar Qim means “standing stones”, and was the name given to large megalithic stones protruding out of an earth mound. A place surrounded by mystery and often referred in former times to be of Phoenician origin. Standing on a rocky plateau a mile away from the village, the site stands gracefully overlooking the sea as if protecting the village of Qrendi.

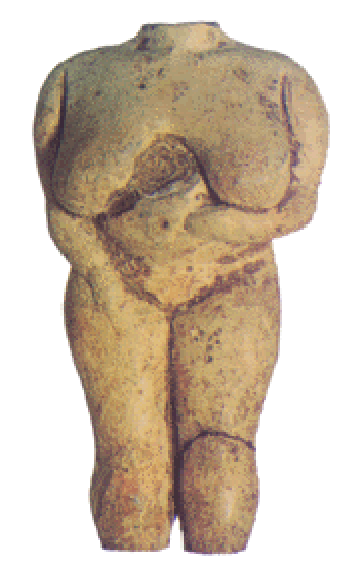

Mr. J.C. Vance of the Royal Engineers explored this interesting archeological site for the first time in 1839. Within two short months of conducting this investigation, Vance discovered a stone altar, a beautifully decorated slab and several stone statutes that were sent to the archeological museum in Valletta for restoration and preservation. Vance further surveyed the site, releasing its great importance and discovered in one of the temples central courts, several other obese stone statuettes of women, a beautifully decorated stone altar with deep carvings representing a plant on each of its four sides together with a stone slab with spirals in relief.

In 1885 Dr. A.A. Caruana carried out further investigations together with Dr. Philip Vassallo of the Public Works Department who made out a lengthily report and published elaborate plans, sections and views. Consequently in 1910, members of the British School at Rome carefully and accurately searched the ruins and the surrounding fields containing the previously excavated debris. These members additional repaired a number of damaged structures and made a rich collection of pot sheds, flint implements, stone and clay objects. The purpose of these investigations was also to establish whether further ruins could be present in the near vicinity. Further examinations were carried out in 1908 by Tagliferro, Ashby., Peet and Sir Themistocle Zammit

A description of the Hagar Qim temple is reproduced from the book “Malta, The Prehistoric Temples, Hagar Qim and Mnajdra” as written in 1931 by Professor Sir Themistocles Zammit who was rated as “The great archeologist of Malta”.

The Hagar Qim monument consists of a series of buildings of the type of the other Maltese megalithic structures. A side forecourt lies in front of a high retaining wall, through which a passage flanked by two sets of deep apses on either side, runs through the middle of the building.

This simple plan was considerably modified. The N W apse was replaced by four enclosures independent of each other, and reached through separate entrances.

The building was evidently a temple, “a place of worship”, in the construction of which great skill was displayed. Architects drew elaborate plans, and an army of workmen directed by expert masons quarried the huge blocks and transported them to the appointed place, smoothed, squared them, and laid them with such consummate art. The accuracy, with which these blocks of stone were set up and fitted together, is really astonishing.

The ruins are approached from the southeast. An extensive forecourt is paved with large irregular slabs, which spreads in front of the outer wall. This solid, but uneven, floor is still encumbered with large blocks that probably formed part of the walls, a striking evidence of past architectural stateliness.

To the right of the forecourt, a mass of disjointed blocks are seen, some still standing in their place and disarranged. Before reaching the main entrance, a stone slab, about 3 m square and 0.42 m thick, was found lying flat on the debris, which covered the floor. In 1930, when the floor was cleared, this slab was propped up. Lying on it is another block 2.2 m by 0.7 m by 0.6m, evidently fallen from the neighboring wall. Local people call this stone the bell, for when struck it emits a ringing sound.

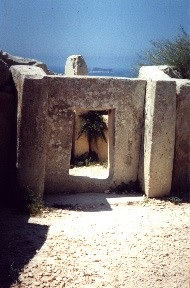

The gateway, in the middle of the façade, is made of two large slabs on end facing each other. About 3 m beyond the entrance is an oval area, which the walls consist of large slabs on end, topped, originally, by courses of masonry. The two apsidal ends are separated from the central court by two vertical slabs, on each side, pierced by a rectangular opening 1.2 m high and 0.9 m wide. These openings, probably provided with curtains, gave access to the side apses.

The central areas are paved with well-set smooth blocks and, along the walls, are low stone altars, originally decorated with pit marks. Some of these blocks are discolored by the action of fire. Important stone objects, now displayed in the Valletta Museum, were discovered all standing about in this court in 1839.

The next area is reached through a passage formed by three large pillars on each side. It is a rectangular enclosure flanked originally by two deep apses, of which, at present, only the eastern one remains, the other having been destroyed when the four independent chambers, or chapels, were devised.

The right apse consists of 18 vertical slabs on which oblong blocks of masonry are built projecting inward as they go higher, so as to form ultimately a vaulted roof. It is clear that these apses were originally domed, but of the vault, only a few courses remain.

At the back of this apse, one of the wall slabs is pierced by an oval hole, about 41 cm from the ground, which opens at the back into a small room, probably the seat of an oracle. These oracular rooms form a prominent feature of the Maltese megalithic sanctuaries. They show that all these places of worship were built with great forethought and that complicated rites had already evolved in the course of the religious life of that primitive people.

Close to this apse, is the second entrance to the monument from the northwest at the end of a 3.6 m passage, well paved and solidly built of slabs on end. To the left of this passage is the entrance to an interesting annex, which is very elaborately constructed with well-smoothed slabs. This small enclosure was, evidently, the holiest part of the temple. On each side of the doorway stands a stone altar of a peculiar shape, with an oblong top and a solid rectangular base.

To the left of the entrance, heavy slabs form a kind of niche in which altars slab is supported by two pillars, 0.9 m above the floor. To the right, a neatly constructed cell contains an altar hewn out of a single block of stone and deeply discolored by the action of fire.

In front of the enclosure, the passage widens into a roughly quadrangular area with an elaborate cell at the end. A slab, blocks the entrance to this cell at floor level, whilst another slab, resting on two pillars, is placed across the top, thus reducing the whole to a rectangular window-like opening. Beyond this window, a kind of cabin was constructed which must have been full of the bones of sacrificed animals and ritually broken pottery. It appears that when a burnt offering was made, the horns or other parts of the sacrificed animal used to be deposited in a cell as a memento of the sacrifice.

At the sides of the western apse three dolmenic structures are built in shallow recesses, two on the southern and one on the northern side. Each of these Trinitrons consists of a well-squared horizontal slab standing on two uprights between 1.5 m and 1.8 m in height. The table stones, broken by fallen blocks, were repaired in 1910, and strengthened by extra pillars built for the purpose.

At the end of the western apse on the left, four steps lead to a well-paved entrance, flanked on both sides by the usual series of slabs on end, and into a room. Whilst at the eastern side it ends abruptly in a slight curve.

To the south, in front of the main entrance, the wall forms a deep recess built up into a polygonal niche by vertical slabs. This recess, once probably covered, is reached through a window-like opening cut in a vertical slab.

Bones of numerous sacrificial animals (oxen, pigs, sheep) were found during the excavation of Hagar Qim, a fact that clearly shows that sacrificial animals were constantly required in the temple.

The remains of a smaller temple are found at about 27 meters to the north of the main building. This smaller building that has suffered greatly from exposure, consisted, originally, of two sets of enclosed areas parallel to each other. Originally a thick wall enclosed the whole building, but of this only some of the foundation stones have survived.

Hagar Qim as seen from in front of the secondary temple